Shaun Killa, the architect behind Dubai’s most photographed building, discusses his latest project, Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab, and how sustainable design shapes the future of luxury hospitality

By Jennifer Choo | September 2025

Shaun Killa’s Museum of the Future is a 77-metre-tall torus covered in Arabic calligraphy, situated in Dubai’s financial district. It is perhaps the most photographed building in a city not short of photogenic architecture.

Killa has spent two decades turning Dubai’s grandest ambitions into steel and glass. Born and educated in South Africa, he arrived in the Emirates in 1998 to work on the interiors of Burj Al Arab. By 2015 he had started his own firm, establishing a practice that combines environmental innovation with bold design—the Bahrain World Trade Centre was the first skyscraper to generate its own power through integrated wind turbines.

His latest project, Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab, brings that approach to luxury hospitality. The hotel, designed as a futuristic superyacht, cuts energy consumption by 40% through self-shading balconies while completing Dubai’s beachfront architectural narrative. In a city where architects compete to build the tallest, fastest, and flashiest, Killa has carved out a reputation for substance beneath the spectacle.

Tatler Homes spoke to him about maritime inspiration, technological innovation, and creating timeless architecture in a fast-moving city.

Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab reflects a maritime elegance inspired by superyachts. How did you bring that idea to life in the design?

The starting point was to honour both Dubai’s maritime heritage and the narrative already established along this shoreline. Jumeirah’s beachfront story begins with Madinat Jumeirah, rooted in traditional forms, then transitions through Al Naseem’s modern minimalism, before moving into the sail-shaped Jumeirah Burj Al Arab and the wave-inspired Jumeirah Beach Hotel. Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab is the final chapter in this trilogy, expressed as a futuristic superyacht. Its double-curved forms, sweeping terraces, and fluid lines capture the sensation of a vessel moving out to sea. Positioned between a private marina and an extended beach, the resort embodies Dubai’s seafaring history while redefining the future of luxury hospitality. It’s not just a building; it’s the culmination of a journey that connects past, present, and future in one architectural story.

You’ve used some really advanced 3D modelling and façade technology on Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab. How does technology shape your design process from concept to construction?

Technology allowed us to turn ambition into reality. The complex double-curved façade and the 36-metre steel arch framing Jumeirah Burj Al Arab demanded parametric tools, robotics, and CNC fabrication. These systems gave us the precision to achieve fluidity without compromise, ensuring the building performs environmentally as well as aesthetically. For me, technology is never for spectacle; it’s about enhancing experience and performance. It allows intuition and hand sketches to evolve into structures that are timeless, buildable, and enduring.

Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab isn’t just a hotel; it’s a whole experience with its spa, multiple pools, and 11 unique restaurants. How did you approach designing a space that feels both luxurious and welcoming, while offering a diverse range of experiences under one roof?

Luxury today is about freedom of choice and moments of discovery. At Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab, the guest journey was choreographed like a performance, dramatic arrivals, fluid transitions, and spaces that unfold in contrast. The arch frames Jumeirah Burj Al Arab with a sense of awe, then guests move through a lobby that feels like the bow of a yacht, into terraces, gardens, pools, and dining concepts that shift in atmosphere. Each of the 11 restaurants and bars is distinct, yet they’re bound by a narrative of fluidity and connection to the sea. The aim was to make every experience feel intimate and curated, while still part of a larger voyage.

The Museum of the Future’s iconic void symbolises the unknown. How do you approach embedding deep symbolism into your architecture without compromising functionality?

Symbolism must always serve a purpose. The Museum of the Future’s void is a metaphor for the unknown, but it also defines spatial clarity and ensures daylight penetrates the atrium. We embed meaning into form only when it aligns with performance, experience, and constructability. To me, architecture should never be ornament for its own sake; it must work on multiple levels: technical, symbolic, and human.

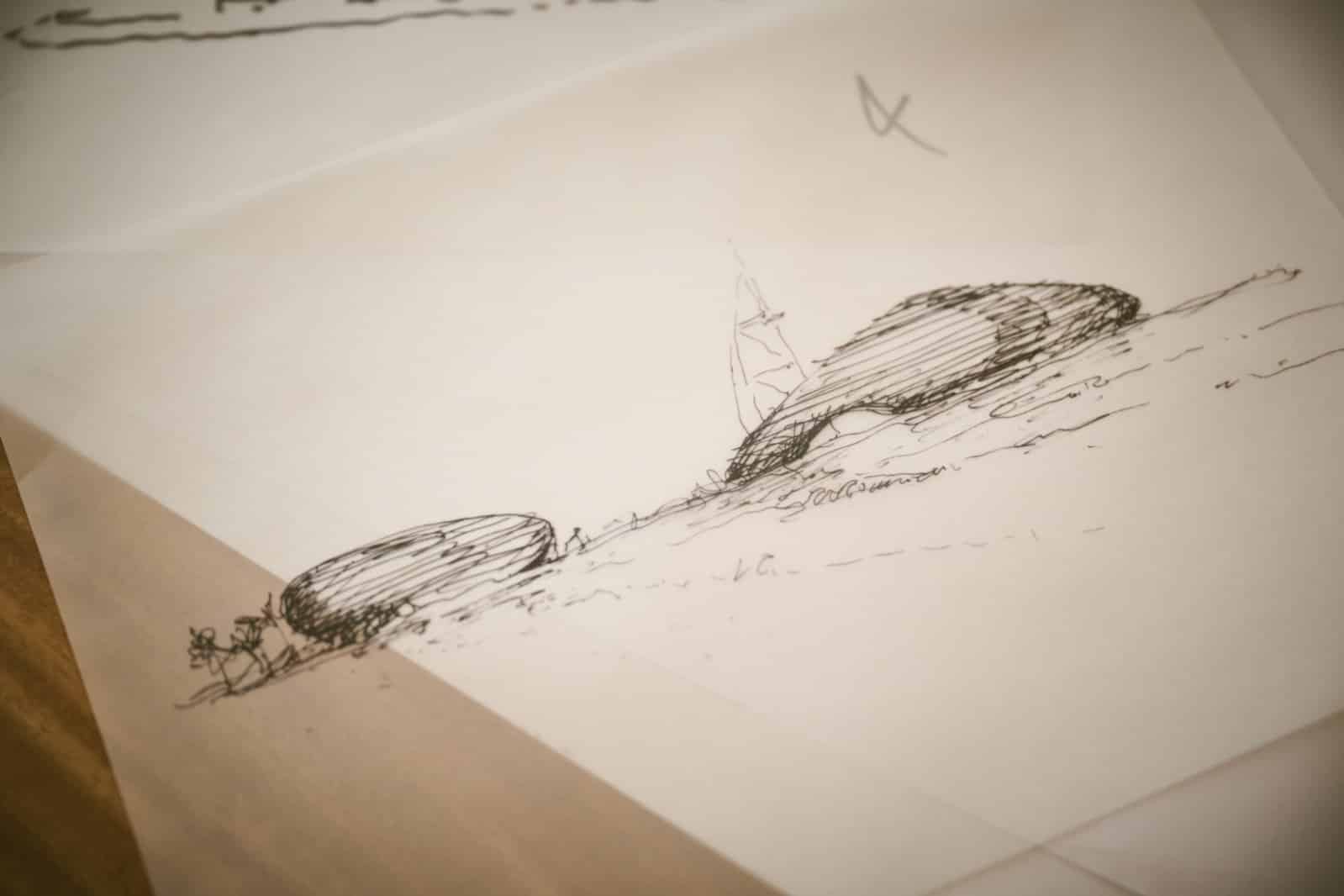

I read that your first sketch of the Museum of the Future was done late at night by hand. Can you describe your ideation process and how intuition and technology interact in your work?

At the end of 2014, I was invited to join the international competition for the Museum of the Future. For weeks I explored options, but none captured the ambition set by the UAE Vice President and Prime Minister. One evening, I cleared the page and began again. In a late-night sketch, I captured the torus form, the calligraphy, and even the landscape podium in one gesture. It was a moment of instinct meeting imagination.

From there, intuition gave way to technology. Together with my team, we used advanced parametric tools and optimisation models to refine every detail, from the diagrid structure to the calligraphy and façade. Robotics enabled the complex fabrication, turning what began as a hand-drawn idea into a buildable reality.

For me, design always begins with a sketch, when ideas are at their rawest. But it is technology that tests, evolves, and realises them. The Museum of the Future is a testament to that balance: a vision born from intuition, made possible through the most advanced tools of our time.

Sustainability has been a core theme in your projects, such as the Bahrain World Trade Centre, which features wind turbines. How do you balance pushing the boundaries with making sure your buildings are environmentally responsible?

For me, pushing boundaries and sustainability are inseparable. At Bahrain World Trade Centre, I pioneered integrated turbines; at Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab we created self-shading balconies that cut energy demand by 40%, greywater recycling systems, and landscaped roofs to reduce the heat island effect. True innovation means designing with empathy, for place, for people, and for the environment. Luxury should not come at nature’s expense; it should enhance quality of life while minimising impact.

Dubai is renowned for its bold and ambitious architecture. How has working here shaped your approach to design? Has the city influenced what you aim to create?

Dubai has given me the freedom to dream bigger. This city doesn’t just accept ambition, it demands it. But with that comes responsibility, to design icons that endure, not novelties that fade. Dubai has taught me to think on a scale of legacy: to create architecture that captures the spirit of its time while remaining relevant for decades to come. It’s a place where tradition and modernity meet, and that duality shapes everything we design.

You lead a team of young architects at Killa Design. How do you encourage fresh ideas and creativity while keeping your projects consistent and focused?

I believe in creating a studio culture where curiosity thrives. Young designers bring fearless ideas, and I encourage them to sketch, experiment, and question. But creativity is channelled through discipline; we align every idea back to purpose, context, and narrative. That balance between freedom and rigour ensures our projects feel fresh yet cohesive. It’s about nurturing a collective creativity within a strong design ethos.

Dubai is constantly evolving, with new, futuristic buildings emerging continually. How do you create designs that feel timeless in such a fast-moving environment?

Timelessness comes from honesty. A building is timeless when it responds authentically to its context, climate, and culture. At Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab, the design grows from the sea and Dubai’s maritime story, ensuring it belongs here rather than chasing trends. Timeless architecture adapts, welcomes, and resonates, it’s as meaningful in fifty years as it is today because it’s crafted with integrity and intent.

Looking back over your career, from early projects like Jumeirah Burj Al Arab to what you’re doing now, how has your design philosophy changed? Are there any ideas that have stayed with you all along?

When I worked on Jumeirah Burj Al Arab, the focus was on creating icons that defined a city. Over time, my philosophy has evolved towards architecture that not only inspires visually but uplifts people’s lives, connects with nature, and gives back environmentally. Sustainability has always been my true passion, from pioneering integrated wind turbines at the Bahrain World Trade Centre, to embedding energy-saving systems at Jumeirah Marsa Al Arab, and achieving LEED Platinum certification at the Museum of the Future. For the Museum, sustainability was a driver from the very first sketch: we used passive solar design, low-energy and low-water engineering solutions, recovery strategies, and renewables from an off-site solar farm. More than two-thirds of the building sits below a landscaped podium roof to reduce solar gain and heat island effect.

What hasn’t changed throughout my career is the belief that architecture must be both innovative and responsible; it should evoke emotion, endure in meaning, and serve future generations.